Where is the moral high ground?

on hypocrisy and harm

Judgement everywhere

Sitting at a cricket stadium where I sometimes co-work, I was pondering the main sponsor of the stadium. A sports betting company.

It probably doesn’t come as a shock if you’ve read anything I’ve written. I’m constantly analysing and judging, looking for right and wrong. My mind went in loops about all the negative associations around sports betting. In my view, it’s gambling on steroids, specifically targeting and taking advantage of the poor.

A few days later, I went for a meal at a friend’s house, only to discover his housemate works for that company. I felt it immediately—the tightening in my chest, the silent judgement forming. My eyes often reveal what’s going on behind them. In this case, I hoped they didn’t. What do you say to someone whose livelihood depends on something you have judged to be predatory?

I’m consistently confronted when these internalised judgements surface. The more I move through life, the worse it gets as I get exposed to real-life data. It wasn’t until I dated someone whose parents were alcoholics that I realised just how debilitating alcohol can be. This led me to examine data on foetal alcohol syndrome and gender-based violence, both endemic in South Africa. Now, in the back of my mind, I associate alcohol with fear and domestic violence, completely messing up lives. Naturally, this association colours how I see the alcohol industry at large.

And frankly, I don’t know what to do about it. Whilst this is part confession, it’s really a broader part of searching for a congruent way of living in the world.

The other side of the coin

Because I know it’s not that simple.

There are of course benefits to these industries. They create economic value, sponsor sports, entertainment and the arts, and their corporate social responsibility efforts give back millions of rands to communities.

In South Africa, the alcohol industry sustains nearly 500,000 jobs across its value chain, from agriculture to retail, and generates R215.5 billion in household income.1 The gambling industry provides over 30,000 direct jobs and supports over 144,000 indirect jobs.2 We can’t pretend these numbers don’t matter in a country with 33% unemployment.

On a personal level, I look back with fondness on the times that alcohol has served as a positive social lubricant. Sports betting has also been fun the few times I’ve dabbled. Every time a football or rugby world cup comes around, I back a few teams to pique my interest, and I’ve yet to lose money.

Perhaps I’m wrong—maybe most people have healthy relationships with alcohol and betting. But my judgement, shaped by the stories I’ve heard, makes me uneasy. I suspect I’m in the minority, that most people struggle more than they’d admit.

And does economic expediency justify harm?

Being complicit

I don’t consider myself a Buddhist, but I think Buddhism provides a good system of values for living.

In the Buddhist tradition, there are three core limbs: morality (sila), meditation (samadhi), and wisdom (panna).

Within morality, there is the concept of right livelihood. It’s about earning a living honestly and ethically, without causing harm to others. But it also means avoiding killing—of all beings.

And here, let me flip the scrutineer’s lens on myself, because if I truly followed these precepts, I would be vegetarian. But I’m not.

I have my justifications for it, and they serve me. I’ve tried to go vegan before, and I lost weight, felt terrible and bloated, and had low energy. If I’m really honest, I don’t want to put in the extra effort of preparing vegetarian meals. I also believe that meat is an important part of a balanced diet. Frankly, I also like the taste.

In an ideal world I’d love to eat meat that has been slain by my own hand or the hand of my tribesman, who has honoured the life of the animal. And yet I go into the local supermarket, and I buy my lamb chops. In small ways, I’m still trying to honour death. I’m making it a practice to give thanks to the life of the animal that has ended up on my plate.

Justification? Definitely. Because there’s a small part of me that feels guilty (and jealous) when I meet people who are vegetarian for ethical reasons. So yes, I’m complicit.

It’s a complicated world. You can’t even invest in the S&P 500 without being implicated. The index is full of companies which profit from addictive patterns, such as MGM Resorts’ casinos, Brown-Forman’s whiskey brands and Philip Morris’ tobacco empire.

How should we participate?

It’s all too easy to hide behind the abstraction of a limited liability company and the gymnastics of fiscal justification. These are, unfortunately, realities of being human in the modern world. And many people likely enjoy their alcohol and gambling in moderation.

But where does one draw the line? If it were your brother or sister, mother or father in the throes of addiction, how would you reconsider your participation in the industry?

I won’t pretend I’m clean. I’m a hypocrite trying to be a slightly better hypocrite. Here’s what that looks like in practice: I invest money in index funds, but I won’t invest in these companies or industries directly. I won’t work for these industries, even if they pay well.

Is that enough? For me, for now. It’s what I can do without retreating to a cave where I’m morally pure and practically useless, whilst I search for ways to bridge the world and the cave.

Perhaps most importantly, even though I draw the lines for myself, I endeavour to practise grace. To continually soften my response to others, because the world is complex, and if I were to truly know the downstream consequences of all my actions, I’m sure I would be horrified. It’s not black and white.

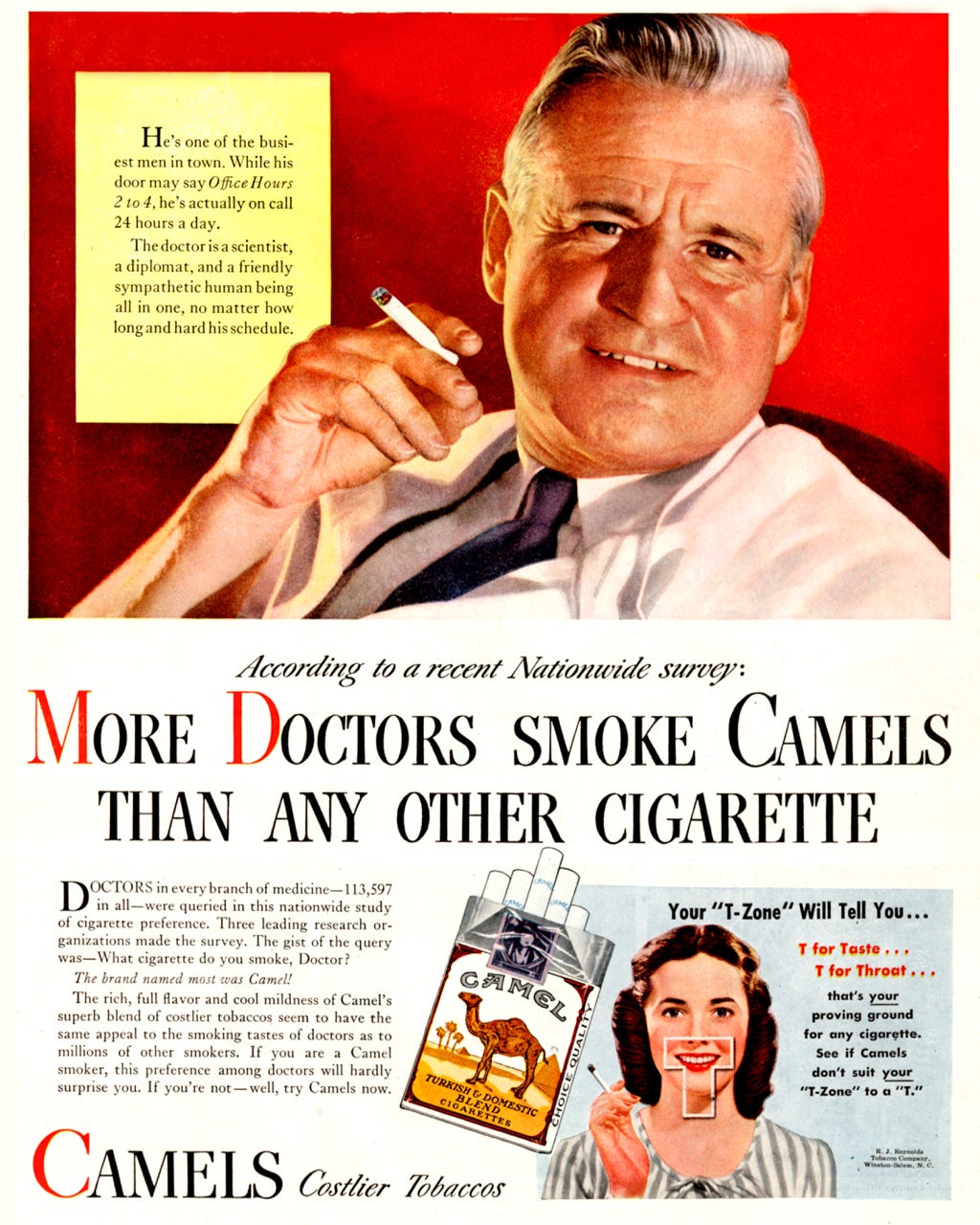

Either way, I have a bold prediction. Or maybe it’s a hope. In 30 years I believe we’ll look back on today’s alcohol and sports betting advertising the same way we now cringe at doctors endorsing Camel cigarettes.

That, at least, will be a win.

https://www.bizcommunity.com/article/drinks-federation-of-sa-launches-report-on-the-alcohol-industrys-role-in-the-sas-economy-035845a

https://africa.businessinsider.com/local/markets/south-africas-gambling-industry-nets-dollar80-billion-despite-economic-pressure/yp558et

What I find useful is that the Buddhist ethical guidance is directional, not absolute (different to the commandments). There is space and grace for imperfection (by contrast, perfectionism is a feature of supremacy culture).

Judgement is also understood as a pattern of mind - which protects us from feeling. To come closer to internal coherence, we need to notice when judgement arises, notices the embodied sensations and then work with safety and breath to stay present and allow the underlying feelings to arise. What would become possible if you slowed down, dropped out of the mind and allowed your heart to really connect with deep compassion with the suffering you describe? This compassion can be enough to ripple change into the world without needing to judge or change others.

In my experience (I struggle with judgement a lot), judgement is most akin to aversion (one of the five hindrances). Understanding it as a hindrance has really helped me find ways to work with it (without unleashing more judgement by judging the judgement!! The teaching of the arrows!)